The alarming image from this week’s UAE Tour was Fabio Jakobsen’s front tyre with the foam insert ripped clean off his rim after hitting a rock at speed. It once again opens the debate on hookless vs hooked rims, and forces us to look bluntly at the safety margins with hookless road wheels.

The wheel supplier Ursus, describes the rim as a mini-hook profile, and while some might argue a mini-hook profile provides a hook for the tyre bead to grip, I would suggest that it bears a closer resemblance to a hookless system. It provides less security for the tyre bead than a traditional hooked rim bed.

In the hours and days that followed the incident, social media and forums once again lit up with debate. Some saw it as a freak accident; others saw it as confirmation of long standing concerns about hookless systems. It’s easy to be reactive, but this incident matters not just because it involved one of the sport’s best sprinters, but because it encapsulates a tension that’s been building in road cycling for years.

Where once there was broad consensus and stability – hooked rims were just how it was done – there now appears to be a gap between standards, manufacturer advice and what riders actually do on the road.

Hookless vs hooked

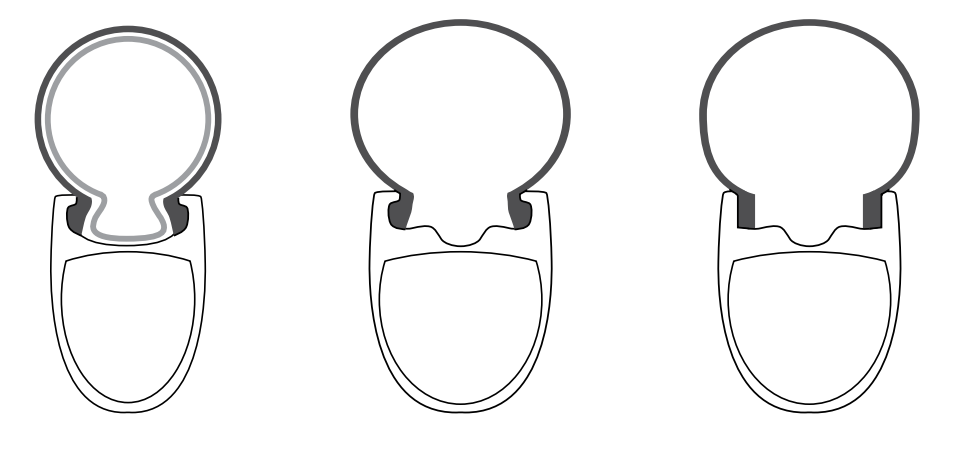

At the heart of it are two competing designs: the tried and trusted hooked rim and the newer, sleeker hookless rim. In mountain biking, where wider tyres are ridden at lower pressure, hookless is favoured. But the controversy continues in road racing, where tyres are narrower and pressures and speeds higher.

One of the most revealing comments from the conversations I’ve had with various wheel and tyre experts is how the ETRTO standards – the formal rules that underpin rim and tyre compatibility – are widely misunderstood or ignored by consumers, and in some cases, in marketing material from the brands themselves.

According to ETRTO guidelines, a hookless, Tubeless Straight Sidewall (TSS) rim has strict inflation limits: the maximum tyre pressure it can be used with is 72.5psi (5 bar), and tyres must withstand more than 110 percent of that pressure in a retention test to be considered compliant.

Without a traditional hook to physically hold the tyre bead, the system relies on tight tolerances in the rim and tyre and on using the correct pressure. Go above those limits and the risk of the tyre unseating grows.

Yet some tyre manufacturers’ guidance doesn’t always make that clear. Websites and pressure tools from brands like Pirelli deliver recommended pressures that vary by rider weight and tyre size, but these can exceed the ETRTO hookless limits.

I tried a variety of combinations on the Pirelli tyre pressure calculator myself. My inputs are relatively typical: 87kg rider, 7kg bike, 25mm tyre, on a 21mm internal, hookless rim with a tubeless tyre. The calculator advised 90psi. If I adjusted the inputs to ‘smooth tarmac’, it suggested 99psi, or 6.8bar. That’s 1.8bar over the ETRTO limit.

That’s not malicious, it’s simply a product of disparate guidance that hasn’t been aligned. But it is dangerous. To illustrate how serious this conceptual gap can be, one tyre manufacturer told me that the system, hooked or hookless – only works when everything is right. If you have the right tyre, the right rim, the right pressures and you stick to the correct limits, both systems can be safe.

“You have to be aware of the setup you’re riding. Yes it can work, but the margin for error is smaller than with a hooked rim.” they said, adding that many riders simply don’t appreciate how tight those margins are unless they actively seek out the information.

One wheel engineer I spoke to has moved his company away from hookless for road products. While they believe that hookless designs can be robust and are confident in their stress testing, a rider who over-inflates or mismatches tyres and rims is more likely to have a catastrophic issue with a hookless system than with a hooked one.

“Hookless rims are technically robust,” he explained. “But the margin for error is smaller than with hooked rims, especially on narrow, high-pressure tyres. If a rider is inexperienced or inflates incorrectly, hooked systems offer a wider safety buffer.”

That engineer’s company had been an early supporter of hookless design, but customer feedback and real-world incidents have driven a pivot back to hooked rims. It’s one thing to believe in a technology’s theoretical performance advantages, another to double down on it when it has safety implications that real riders must manage.

Specialized, for it’s part, has stuck consistently with hooked systems on the road. Their spokesperson was clear that hookless setups have their place, but the company’s product portfolio reflects a belief that hooked rims remain a better fit for a broad range of riders, especially where safety and tolerance for setup errors matter most.

(Image credit: Getty)

And then there’s the UCI – the sports governing body – which has weighed in before on related safety concerns after previous blowouts involving hookless and tubeless combinations. Two years ago, following a high-profile crash at the UAE Tour, attributed in part to tyre retention issues, the UCI launched a review with the stated aim of protecting rider safety and clarifying guidance around hookless use on road bikes.

What unites all these view points – engineers, tyre makers, standards bodies, governing institutions – is a shared emphasis on one thing: consumer education. Nobody I’ve spoken to argues that hookless rims are fundamentally unworkable. The issue is that most riders do not treat rims, tyres and pressures as a tightly coupled system that needs to be carefully managed.

That’s not that surprising. 15 years ago, tyre pressures of 100-plus psi on a 23mm tyres were commonplace, and many are confused by a proliferation of calculators, recommended pressures, tyres widths and competing narratives about performance. Our own guide to these tyres notes the complexity of the situation and urges riders to use pressure calculators from trusted brands and abide by the ETRTO/ISO recommendations, or simply choose hooked rims if they want the easiest path to a safe setup.

It is this gap – between what the standards say, what manufacturers’ advice suggests and what riders actually do – that has turned what might have once been a niche technical debate into something that affects more and more cyclists. The more we rely on pressure and tight tolerances to hold tyres in place, the more important it becomes that riders understand exactly what they’re doing when they mount, inflate, ride and monitor their wheel systems.

Let’s be clear: catastrophic tyre blow offs are rare. Tens of thousands of people ride on hookless rims without incident. But rare events like Jakobsen’s crash – and previous WorldTour incidents – act like alarms. Not because they prove that hookless is unsafe, but because they expose how little margin there is for mistakes when pressures creep above safe limits, or when, as is clear in this case, rocks and high speed impacts occur.

Tubed clincher, tubeless hooked, and tubeless hookless, showing the shape of the rim bed in each case and the way the tyre is retained.

(Image credit: Future)