Cub Swanson saw the inside of many medical facilities during his two decades as a pro fighter.

“I’ve probably been to over a hundred different doctors,” Swanson says. “I’ve had about 40 MRIs. Probably close to that many CT [scans]. Lots of physical therapy. You get to where you almost feel like you’re becoming an expert on it yourself.”

Advertisement

No one who decides to pursue a life inside the cage thinks they’ll get out unscathed. In the hurt business, everybody has to take their lumps.

But the viewing public doesn’t always realize what a human body must endure for the sake of this career. We see the blood and the bruises on fight night, sure. So many of the injuries in fight sports occur in training, though. Even with the ones we do see on television, the surgeries, rehab and lingering effects all happen off-screen.

You might have heard, for instance, that Swanson injured his hand (again) during his dramatic final fight against Billy Quarantillo at a UFC Tampa event late last year. Chances are the information drifted in and out of your mind, replaced by other injury news affecting other fights and fighters.

Swanson has been dealing with it as more than a throwaway mention on some report. And the injury is healing nicely, thank you very much. It took him about only six months before he could finally hold a glass of water with that hand again.

Advertisement

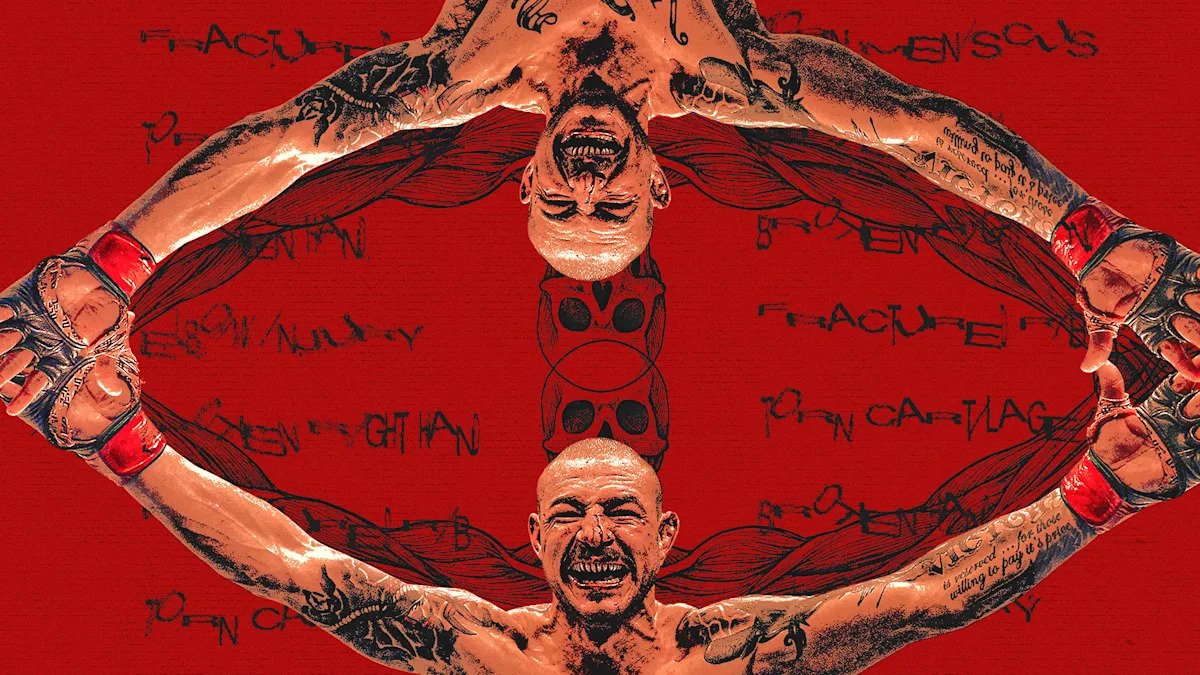

This is the story of Swanson’s 20 years in the fight game, as told by his battle wounds. His was not a particularly injury-prone career. All the things that happened to him also happened to others. Some had it worse, others somewhat better. But after 44 professional fights, Swanson’s body tells a story. Each pin and plate, each scar, all come with a separate memory of pain and sacrifice — and the decision, made over and over again, to press on.

Cub Swanson scored a dramatic knockout victory in his final UFC fight in December 2024.

(Chris Unger via Getty Images)

Of all of Swanson’s notable injuries, the first one was the most bizarre. It came just a couple fights into his pro career, back when he got all his training at one jiu-jitsu gym.

“It was only open four days a week, and when I was backstage for my first fight I’d heard all these guys from Orange County talking about training two or three times a day,” Swanson says. “I remember thinking, ‘Man, how am I going to keep up with these guys if I don’t train more?’”

Advertisement

So with a fight coming up four weeks later, Swanson talked a training partner into joining him at a nearby park so they could get some rolls in on the wide-open lawn. It sounded like a good idea at the time. Then he hit his knee on a sprinkler head and “split it open to the bone.” Maybe not such a good idea after all.

It obviously needed stitches, but the fight was four weeks away and the jiu-jitsu gym he trained at started every sparring round on the knees. How could he keep training with stitches in his knee?

“So I thought about the movie ‘Rambo,’” Swanson says. “And I just took a butter knife, heated it over the stove, and I cauterized it myself. Then I bandaged it up and kept it really clean and trained every day and just sucked it up through the pain.”

If you’re wondering, didn’t that hurt? The answer is yes, a whole lot. First he tried to get his brother to do it for him, but that resulted in splitting the wound open wider. Then he decided to grit his teeth and do it himself, but even that took two or three tries.

Advertisement

He won the fight, though. In fact, after losing his pro debut, he won 11 straight fights.

His seventh pro fight was a rematch with Shannon Gugerty, the man who’d handed him his first loss. Swanson always wanted to get another crack at him after losing via quick submission. When they met again nearly two years later, Gugerty tried for another submission, rolling for a heel hook. Swanson defended and then tried to make him pay for the attempt.

“I went to punch him, but because I was at a weird angle, I only landed with one knuckle and it broke my hand,” Swanson says. “I knew right away. I had to have surgery — that was my first metal plate — but it was a tough one because it was covered by the insurance of the company I fought for, but the way it worked was you had to pay out of pocket and then they’d reimburse you. I had to borrow money from somebody I really didn’t want to have to borrow money from, and then [the insurance company] didn’t want to reimburse me. It ended up working out, but it was tough.”

Hand injuries would be a recurring issue for Swanson. He’s not alone. MMA’s small gloves provide minimal hand protection in fights, and the exposed fingers offer more ways to injure oneself. Swanson got a hard lesson in those risks just before he fought John Franchi in the WEC.

I thought about the movie ‘Rambo.’ And I just took a butter knife, heated it over the stove, and I cauterized it myself. Then I bandaged it up and trained every day and just sucked it up through the pain.

Advertisement

It was a week or so before the fight and he was training with Diego Brandao, who would later win Season 14 of “The Ultimate Fighter.” They were drilling together inside the cage after a practice session concluded, and Brandao pushed Swanson backward with a sudden double-leg attempt.

“I was bouncing on one foot, and when I reached back I knew I was coming close to the cage, but then my hand went into the cage, like through the chainlink,” Swanson says. “I didn’t realize I was so close, and we fell on my hand and it snapped where my finger attaches to my hand. I basically broke a piece of bone off of my finger and my hand swelled up all big. I went to the doctor and they said it was broken, but I still needed to fight.”

This was a common problem, especially in that era of MMA. You get hurt in training, but maybe you don’t have health insurance. If you can make it to the fight, you can use the promoter’s fight night insurance to get your health needs seen to, since it’s entirely believable that your broken hand (or whatever) was sustained in the fight itself.

But then Swanson faced another problem. He started the fight with an injured right hand, then earned himself another when his left landed awkwardly on Franchi’s skull in the second round.

Advertisement

“So then I had two broken hands,” Swanson says. “I still beat him, though.”

All told, Swanson would suffer a total of 14 different fractures in his hands over the course of his career. He has three metal plates in his hands, including hardware in both thumbs. That first plate, the one from the first year of his career, is already on borrowed time, according to doctors he’s seen. The ligament runs over the plate, which one surgeon compared to having a length of rope slowly sawing against a wooden board. One day, Swanson has been told, it will snap.

“So I just try not to use that finger,” he says. “If I’m playing video games with my kids I’ll notice it. It gets irritated if I use it too much. You just get used to not using that one.”

Cub Swanson’s victory over John Franchi at WEC 44 came at a cost.

(Josh Hedges via Getty Images)

And then there was the broken jaw. Which, even putting it like that doesn’t quite capture the entirety of the thing, since it involved his entire face and not just that critical lower portion of it. This, too, was one of the many traumas of the training room. It was also entirely avoidable, which is what still bugs Swanson about it today.

Advertisement

The short version of the story is that he was sparring with teammate Melvin Guillard at the Jackson-Winkeljohn gym in Albuquerque one day when Guillard launched into a flying knee that caught Swanson by surprise. One of the reasons for the surprise was that kneeing teammates in the face with full, sudden force is generally frowned upon in practice. The fact that Guillard did it might be indicative of the reasons why, years later, Guillard was explicitly told that he was not welcome at the gym.

The knee caught Swanson flush. It didn’t knock him out, but he knew right away he had problems. When he went to remove his mouthpiece, he could feel his teeth moving with it. As he felt around in his face, he noticed what felt like a bone sticking through his gums. A sharp pain spread up into his cheek. This was starting to feel like the kind of thing that would have to be sorted out at the hospital.

The final tally was worse than he feared. Seven fractures in his face. A broken jaw that would have to be wired shut for six weeks. A broken orbital bone that would require reconstructive surgery. The insertion of two more metal plates — one in his cheek, one outside his left eye. And just for fun, in the process of inserting one of those plates, the surgeon hit a nerve in his face, creating an odd sensation that he still feels at certain times.

“One of my teeth has been asleep ever since the surgery,” Swanson says. “I remember telling the doctor, ‘This tooth right here, it’s weird, it feels asleep.’ And he was like, ‘Oh yeah, I probably hit a nerve. It’ll probably turn black and fall out.’ He was just so nonchalant about it. And I just was like, ‘What?’ But luckily it never did. I think I was very fortunate.”

Cub Swanson dealt with plenty of injuries over his two-decade career, but none were more horrific than his broken jaw.

(Jeff Bottari via Getty Images)

The physical damage was bad, but the psychological torment over the ensuing six weeks was worse. With his jaw wired shut, Swanson couldn’t eat solid foods. He had to practically shout to be understood. The doctor gave him a prescription for liquid Percocet. He took one dose, but it made him nauseous. And when you can’t open your mouth, a little nausea could end up becoming a huge problem.

Advertisement

“I woke up in the middle of the night and I felt like I was going to throw up,” Swanson says. “And they had told me, ‘If you throw up, well, your jaw is wired, so you might die.’ There’s nowhere for it to go. You could suffocate, so you’ve got to cut the wires off. Then I’d have to go back to the hospital and do it all over again. You’re supposed to carry pliers around with you, which I never did. Having that happened in the middle of the night, it kind of scared me. I was alone. And then the next day I was like, ‘Man, all [the pain medication] is going to do is make me feel sorry for myself and depressed.’ So I flushed it down the toilet and I was like, ‘Alright, I’m not doing that.’”

There was another part of it that bothered him. As he was at home recovering from his injuries, he felt increasingly isolated. The gym was where most of his social life happened, where his friends were. But those teammates who were so important in his life seemed to disappear once he got hurt, which was difficult to understand at first.

“I remember not really hearing from anybody and feeling very alone,” Swanson says. “And I realized that fighters, they have that fault. They think: It can’t happen to me, it won’t happen to me. They feel the bad stuff and know it’s possible, but you can’t let that seep in. You have to put up these blinders because you have to feel confident. You have to feel secure and ready. If somebody you know gets hurt, you don’t want to think about it too much but you need to believe it won’t happen to you. You have to convince yourself that you’re going to be able to get through it without that happening.

“So I remember feeling pretty alone in that moment and just realizing, ‘Oh, OK, it’s not that they don’t care about me. It’s just that I had a serious injury.’ And people, they don’t want to face the reality that that’s always a possibility.”

I woke up in the middle of the night and I felt like I was going to throw up. And they had told me, ‘If you throw up, well, your jaw is wired, so you might die.’ There’s nowhere for it to go. You could suffocate, so you’ve got to cut the wires off.

Advertisement

Swanson battled the isolation and the depression by throwing himself into whatever work he could do. Though doctors had told him not to return to the gym so soon after surgery, he went and walked on the treadmill. Then he ran. Then he went to the boxing gym and hit pads. Bit by bit, he pulled himself out of a deep, dark hole.

The experience changed him forever, he says. It changed the way he approached training and how he viewed the team environment within the gym. It’s carried over to his coaching now that he’s semi-retired and training his own group of fighters with Team Bloodline.

“I am extremely strict in my gym,” Swanson says. “I don’t let people try to hurt anybody. We don’t spar too hard. I have very strict guidelines, and it’s really just because I believe that the problems are because of ego. Guys think, ‘I need to be the best guy in the room, and I’m willing to step on everybody to get there.’ What you should be thinking is that everybody in this room needs to get as good as possible, and we all need to do that together. And I think when you create that environment, you really cut down on the trauma to the brain and the unnecessary injuries. You’ve got to take the ego out of it. Ego is what gets people hurt.”

Swanson would end up suffering a second broken jaw later in his career, which is not uncommon. The first fracture is somewhat rare, but once it happens it increases the odds of another. Both times, he says, he had to face questions about whether this life was worth all this pain and suffering. Some of those questions came from his family, he says. Others came from within.

Advertisement

“Some injuries are worse than others, but I think with all of them you end up asking yourself if this is still what you want,” Swanson says. “This is a tough life. But I think a lot of fighters, they’re searching for something. They have questions about themselves that they want answers to. And this game will teach you a lot of lessons that you don’t even know you need to learn.”

Over the course of his career, Swanson battled multiple UFC champs and top contenders.

(Josh Hedges via Getty Images)

There were other injuries, of course. Little ones. Bigger ones. Some that, unless he really starts trying to come up with a list, can almost slip his mind.

A couple weeks before he fought Dennis Siver at UFC 162, he got kicked in the elbow during sparring. He knew it felt off, but it didn’t seem too bad at the time.

Advertisement

“Then maybe a couple weeks later, I tried to answer my phone and my elbow locked and I couldn’t get it to my ear,” Swanson says.

There were some broken ribs, broken toes, a broken nose. The basic stuff that anyone who straps on the gloves can look forward to at some point. He counted himself lucky to escape without any damage to his knee ligaments, so often an area of major trouble for pro athletes. But then he did a grappling match against Jake Shields at Quintet Ultra and tore his ACL and meniscus.

After knee surgery he again had a doctor pushing pain medication on him. Swanson told him he didn’t need it and wouldn’t take it.

“I think that’s one issue I’ve seen with doctors sometimes,” Swanson says. “They’re always trying to make people not feel pain. But the pain is important. The pain is telling you what your body can and can’t do.”

Advertisement

That’s one of the other things Swanson learned from his many injuries, is how to ask questions and dissect the answers. Whether it’s coaches or doctors, he says, he wants to hear the reasoning behind the recommendations. If they can’t explain it, he doesn’t blindly trust it.

And, as with coaches, some doctors have been better than others.

“A lot of them want to lecture you,” Swanson says. “They’re like, ‘What are you doing to your body?’ But then the back doctor I had, four hours after the surgery he talked me through it and then made me go on a hike with him. He told me, ‘You know your body, so be smart and train as much as you feel like your body can handle.’ He was cool.”

[Doctors are] always trying to make people not feel pain. But the pain is important. The pain is telling you what your body can and can’t do.

It took a long time for Swanson to learn what he needed to about listening to his own body, he says. Those early years of his career, he was so fixated on being the toughest guy in the room. Maybe they all were. Always trying to show themselves and each other what they could take and how much pain they could stand.

Advertisement

“It was an internal thing I had, feeling like I always had to prove that,” Swanson says. “But after I fought Frankie [Edgar] and then [Max] Holloway after that [in 2014-15], I realized I needed to be smarter — not tougher. Everyone in the UFC is tough. Not everyone is smart. Trying to be the toughest guy there, it only gets you so far and you can only do it for so long.”

Swanson’s last fight came in December 2024, just about six months shy of the 20th anniversary since his pro debut. You don’t stay in this sport that long without being tough, but you also don’t last that long without learning a thing or two.

When he looks back on his career now, that’s what he’s more proud of. It’s the wisdom he gained, much of it the hard way, that he can now pass on to others. The pain he endured along the way was an excellent teacher, in that sense. But he’s hopeful that the next generation of fighters won’t have to endure quite so much of it. Not if they’re willing to listen and learn from those who have been there.

“But some people, they have to find out for themselves,” he says. “And that’s a thing I’ve had to learn as a coach, is how to let them.”