Memories of Madrid 1986, Another Illness-Impacted World Championships

The Canadian coach’s name didn’t appear, but the line was too good to omit from contemporary reporting.

Read about the fifth FINA World Aquatics Championships, held in 1986 in Madrid, and the line is never far from the lede. For most of the six days of swim competition, the venue wasn’t referred to as the Piscina Centro de Natacion. It was “the vomitorium.”

Many of the nations present at the World Championships, then more or less a quadrennial event since its inauguration in 1973, were hit with bouts of stomach illness. The non-European teams were particularly affected by gastrointestinal difficulties, which, as Swimming World wrote at the time, “moved through some visiting teams like the Wave at the opening ceremonies.” Ultimately, most of the teams that were not the East Germans were adversely affected, their anabolic immunity still in the whisper phase and not to be definitely proven for another few years. (Among the sidebars in the October 1986 edition of Swimming World was one titled, “Kristin Otto: The Natural.” Oops.)

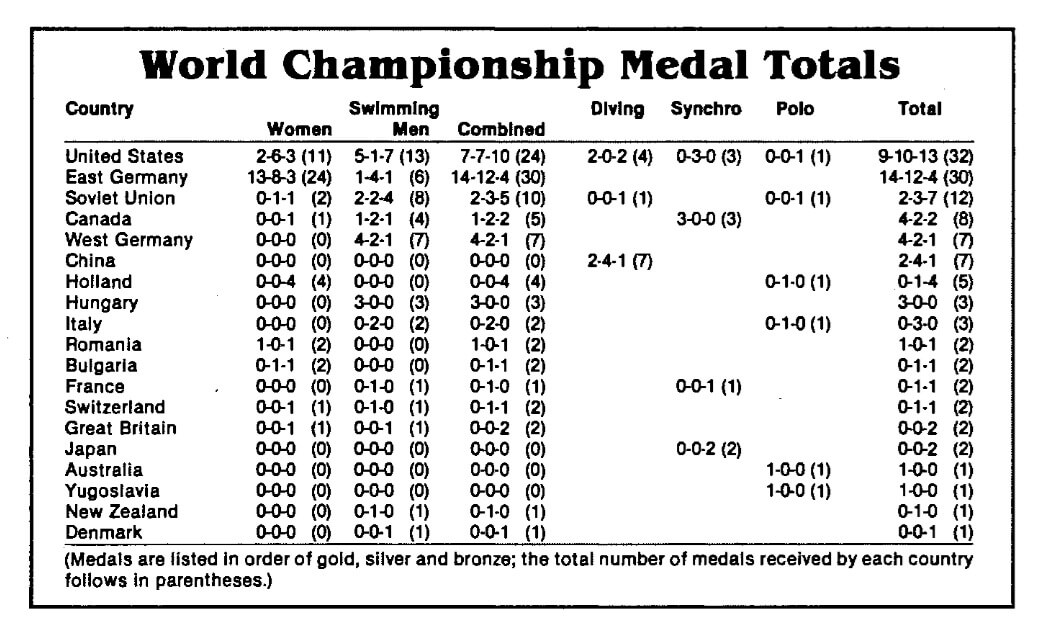

The result was the East Germans winning 13 of 16 women’s gold medals and topping the overall table with 30 medals. From the Americans, among other dour data points, only six of 107 individual swims (and only one male) resulted in personal-bests. It led to recriminations as to what had to change in the American approach and calendar, coming on the heels of a similarly dispiriting performance in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in 1982.

If any of that sounds familiar to the noises emanating from the American camp in Singapore, it should. And while the current case of acute gastroenteritis befalling the U.S. seems isolated to their camp after staging in Thailand, the echoes of four decades ago are useful.

The Spanish Suffering

The anecdotes from U.S. camp in Madrid in 1986 were grim. Like Dave Wharton bookending his race in the 400 IM with, shall we say, rejections of his lunch. Or distance swimmer Mike O’Brien, already standing 6-6 and 175 pounds, somehow finding 13 pounds to lose. Or Steve Bentley ascending the podium for bronze in the 200 breaststroke 10 pounds lighter than when he arrived in Madrid. Or U.S. men’s water polo captain Terry Schroeder having to quash reports that “players were actually taking themselves out of the game against Italy to run to the restroom.”

The Oct. 1986 edition of Swimming World Magazine, which recapped the Madrid 1986 World Championships; Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Magazine

Instead of an assault on the world record boards, the damage in Madrid 1986 was to GI tracts. Just six world records fell in Madrid, all in women’s competition, including two relays. Particularly difficult was the meet’s placement in a competition desert, following two diminished Olympics in which each Cold War power mutually boycotted their opponent’s home Games.

The cause of the outbreak seemed rooted in Madrid, euphemistically considered “traveler’s disease.” Sports Illustrated called it, “a raging intestinal disorder.” Best guesses connected it to food or water consumed by many non-European teams, with the Americans spending nine days in Spain, including an off day smack in the middle of the six-day swim calendar. The fact that the German delegations had their own food preparation and weren’t affected was taken as significant.

Chroniclers struggled to quantify the futility. The U.S. left the meet with seven gold, seven silver and 10 bronze medals. It finished second on the overall medal table to East Germany, buoyed by six men’s medals. The once-dominant American men claimed just five of 13 golds, barely edging West Germany in that category.

“I don’t think any of the kids like to use excuses,” U.S. head coach Richard Quick said late in the meet. “But I think the illness is very real and has affected them significantly.”

The U.S.’s malaise had several potential contributing factors. U.S. Swimming information services director Jeff Dimond listed not only illness but an inexperienced and potentially overtrained team, a slow and cold pool, and the lack of atmosphere at a sparsely attended event. Also pertinent was that the East Germans trained at altitude in Mexico City to prepare for Madrid, which is 2,000 feet above sea level.

Times were slow and performances inconsistent across the board. Only two swimmers – West Germany’s Michael Gross (200 fly, 200 free) and East German Cornelia Sirch (200 back) – repeated as champions from the 1982 meet in Guayaquil. Among the strugglers in Madrid was the USSR’s Vladimir Salnikov, who went from back-to-back world titles in the 400 free to a non-factor fifth, and Pablo Morales, the 100 fly champ and third seed in the 200 who missed the finals in the latter.

The U.S. saw a 30-year streak of placing a male swimmer in every final of a non-boycotted Olympics or Worlds dating back to the Melbourne Olympics in 1956 end … then did it again in the same week. The time required to make the final eight in the women’s 200 free in Madrid was slower than the 12th-place finisher at U.S. nationals. Mary T. Meagher entered the 100 fly with the world record of 57.93, an inimitable mark set in 1981 that would hold for nearly two decades. Five years later, she was two seconds slower, getting bronze in 59.98, reportedly one of the most affected by illness. She recovered to win the 200 fly on Day 6.

“I don’t want to come across that we’re blaming everything on illness,” Quick said. “Everyone’s had problems with it, but it should not be that big of a factor. I don’t think it’s any one thing.”

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Archive

When the U.S. did swim well, the GDR juggernaut was there: The U.S. women were .15 seconds under the world record in the 800 free relay, for instance … but three seconds behind the East Germans. It took until Night Three and Betsy Mitchell’s breakthrough in the 100 back to stop the East German run of golds. About the only bright spot was Matt Biondi, who with the addition of the 50 free won seven medals. Even that, though, was tinged with disappointment, as three were bronze, including the 50 free (behind countryman Tom Jager) and 200 free.

The troubles were compounded, at least once the dust settled, by context. In Ecuador in 1982, the U.S. won eight gold medals, seven silver and 10 bronze. It was regarded as a catastrophic program nadir, with not just a repeat of the GDR’s dominance of the 1970s but ground ceded to the Soviet Union.

Then they went to Madrid and were somehow worse, with one fewer gold and the same quantities of minor medals.

In terms of spirit, Meagher after her 100 fly thought the team was coping. “There’s a little disappointment, but it’s not like it’s real negative,” she said. “It’s been worse. It was worse in ’82.”

Dimond’s reaction differed, as he said three days into the meet: “The loudest thing at breakfast this morning was the snap, crackle and pop of the Rice Krispies. The kids are already talking about going home.”

A Worlds Away

A fair few things have changed in 40 years, among them the candor with which such issues are discussed. (To be fair, the meet ran in August; SI published its recap in its September edition, while it made the October edition of Swimming World. The 24-hour news cycle was only a nightmare not yet dreamed up.)

But parallels remain. The Americans are almost uniformly slower in Singapore than in Indianapolis for Trials, with Kate Douglass and Jack Alexy among the outliers.

The medal table of the Madrid 1986 World Championships

The opening days of the meet brought a pair of event withdrawals – Torri Huske in the 100 fly, Claire Weinstein in the 400 free. Weinstein, who won bronze in the 200 free, seems to have recovered. Huske, who delivered a noticeably slower leg in the mixed medley relay that failed to escape prelims and was part of a favored U.S. team that got silver in the women’s 400 free relay, has not.

When swimmers have gotten to the blocks, some results have been so regressive that illness must be to blame: Luka Mijatovic finishing 36th in the 400 free, Jack Aikins crashing to 44th in the 100 back, 14 and four seconds off their best times, respectively. Forget the Melbourne streak of making finals; the U.S. didn’t even get a man into the semifinals of the 100 back.

This time, the illness is only an American concern. But they aren’t the only swimmers underperforming in Singapore. Pan Zhanle, the world record holder in the 100 free whose mark was arguably the moment of the Paris Games, didn’t make the final of the 100 free. Daniel Wiffen, winner of the 800 free in Paris, was eighth in Singapore. Top seeds without the Stars and Stripes on their caps have come up small. The meet as a whole didn’t have a world record until Leon Marchand in the 200 IM on Night Four. After much hand-wringing about pool speed in Paris, a meet that produced just two individual world records, the debate is mercifully muted this time.

Context again weighs heavy. The United States men’s program is coming off a disaster in Paris, requiring Bobby Finke’s final-day gold in the 1,500 for its only individual title. They’ve escaped that predicament this time thanks to Luca Urlando in the 200 fly. Paris yielded nine total men’s medals (two gold, three silver, four bronze). At one gold, one silver and one bronze through four days, it’s hard to fathom the U.S. even getting close.

What does seem different, though, is the spirit of the team. Beyond Katie Ledecky dead-panning an international reporter with, “what illness?” when asked about it after her 1,500 prelims, the U.S. has tried to take it all in stride.

“I think everyone is staying really positive,” Ledecky said. “It’s a very supportive team. When this all started, everyone just got behind each other and try to laugh it off and give your best effort every time you’re in the pool.”

“I know Team USA got off to a rocky start with our training camp and everything,” Regan Smith said after winning silver in the 100 back. “But that’s something that’s out of our control. We’ve been so positive, and we’ve all bounced back really well.”

Summer School

The summer of 1986 echoed the summer of 1982 at least in how Swimming World processed it. In the editorial leading the Worlds recap, editor Bob Ingram brought the ghosts directly into the light, mirroring what had been written four years earlier in light of Guayaquil and extrapolating the context.

Among the debates were timing of trials meets, the presence of a training camp – one preceded the highly successful 1978 Worlds – and the scheduling of multiple summer peak meets to aim at, including a U.S. Open. (At the time, elite swimmers had trials, Worlds and the Goodwill Games as major competitions between Olympics, a far cry from the constellation of long- and short-course meets on offer now.)

It didn’t save the U.S. at the 1988 Olympics, the low-water mark for Olympic swimming with eight golds and 18 total medals, both second to GDR. But most of the changes broached by the U.S. power structure then were eventually implemented or at least tried and refined, such that they’d be considered low-hanging fruit now.

“If we are to find ways to improve by 1988, we really must begin with the basics,” Ingram wrote then. “Swimming should be fun. Administrative decisions should be made for the swimmers. Competition throughout the summer should be made available.”

The current parallels tend to end there. Most of the changes suggested then are so engrained now as to seem natural, and the U.S. did find a way to become the world’s swimming power again. The proximal concern to avoid a Singapore repeat is how to keep athletes healthy even from low-probability freak situations, something that USA Swimming has surely pondered for decades.

But another downer at Worlds also opens the door for major changes. With two years to the next major international competition and three years until a home Olympics, it may be the impetus for a significant rethink.